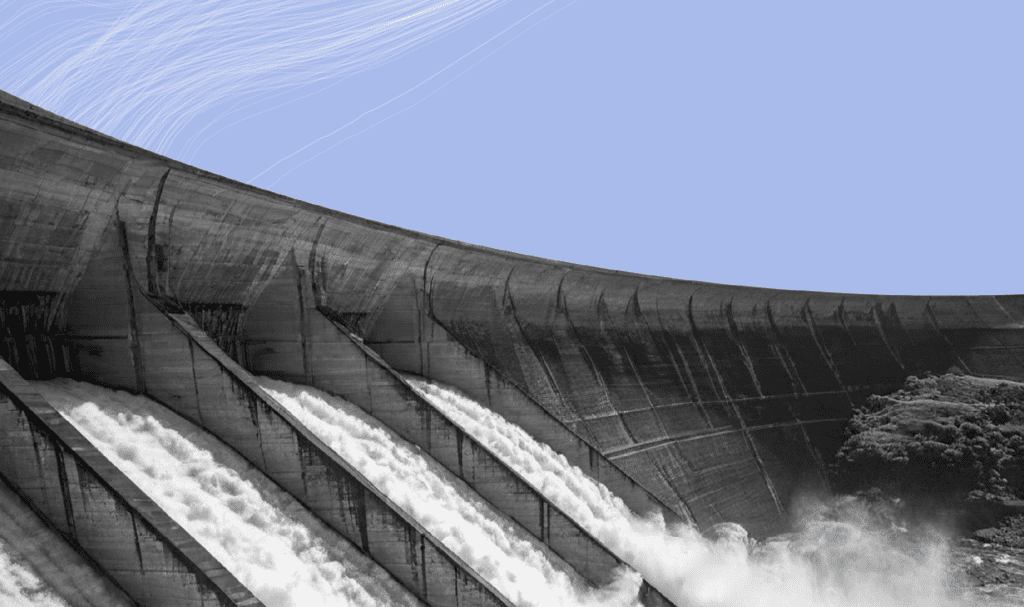

Brazil’s two largest hydroelectric power plants (HPPs), Itaipu and Belo Monte, play essential roles in the country’s electricity sector. With respective installed capacities of 14 GW and 11.2 GW, they account for around 11% of Brazil’s electricity generation capacity. However, the full realization of the plants’ potential depends on water availability in the rivers on which they are located.

Deforestation of the Amazon forest modifies rainfall in hydrographic basins both inside and outside this biome, reducing river flow and negatively affecting the HPPs’ power generation.

Researchers from the Climate Policy Initiative/Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro (CPI/PUC-RIO) and Amazon 2030 have analyzed the impact of changes in rainfall patterns, caused by deforestation, on the electricity generation—and associated revenues—of the Itaipu and Belo Monte HPPs. This analysis has identified that, together, the HPPs are losing 3,780 GWh in energy generation potential per year due to deforestation. This is equivalent to the electricity consumption of approximately 1.5 million people and around US$ 200 million in revenue for the HPPs.

Hydropower has historically been Brazil’s primary source of electricity, accounting for 48.6% of the country’s installed capacity and 60.2% of total generation in 2023.¹ This publication explores two case studies to show how changes in hydrological regimes, as a result of Amazon deforestation, have exposed the vulnerability of Brazil’s two largest HPPs, testing the resilience of the country’s overall electricity mix. Each case evaluates the effects of Amazon deforestation on the respective plants.

Itaipu, the country’s largest HPP, is located on the border between the Brazilian state of Paraná and Paraguay, more than 1,000 kilometers outside the Amazon biome. The plant represents 6% of Brazil’s electricity mix and generated the equivalent of 15.7% of the country’s total energy consumption in 2023.² In that same year, Itaipu HPP’s average loss of annual electricity generation potential, induced by deforestation, was estimated at 1,380 GWh. This translates into a loss of approximately US$ 86 million in revenue per year—around 6% of the plant’s recent annual average profit.

The second case study conducts the same analysis for Belo Monte HPP, Brazil’s second-largest HPP, located in the state of Pará, within the Amazon biome. The plant accounts for 5% of the national electricity mix, supplying 5.9% of all energy used in the country in 2023.³ The average loss of annual electricity generation potential due to deforestation is estimated at 2,400 GWh. This translates into an annual loss of US$ 110 million in revenue—approximately 20% of the plant’s earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization (EBITDA).

The report also identifies the areas of the Amazon that influence the electricity generation of the Itaipu and Belo Monte plants. The area affecting Belo Monte HPP is more concentrated than that affecting Itaipu HPP, which is influenced by air currents with trajectories that extend over several regions of Brazil. Identifying the areas that most affect energy generation can guide better implementation of conservation and restoration policies, allowing the appropriate targeting of resources to mitigate the adverse effects on the energy sector.

The results show that Brazil’s largest HPPs are already being affected by Amazon deforestation. This creates a strategic necessity for the electricity sector to actively participate in the country’s environmental agenda. Greater definition and integration of strategies that reconcile forest conservation and restoration policies with electricity generation policies are crucial for the security of the electricity sector and for boosting forest restoration.

Read the full paper here.